Psychological Reasons Why New Year’s Resolutions Fail

March Issue

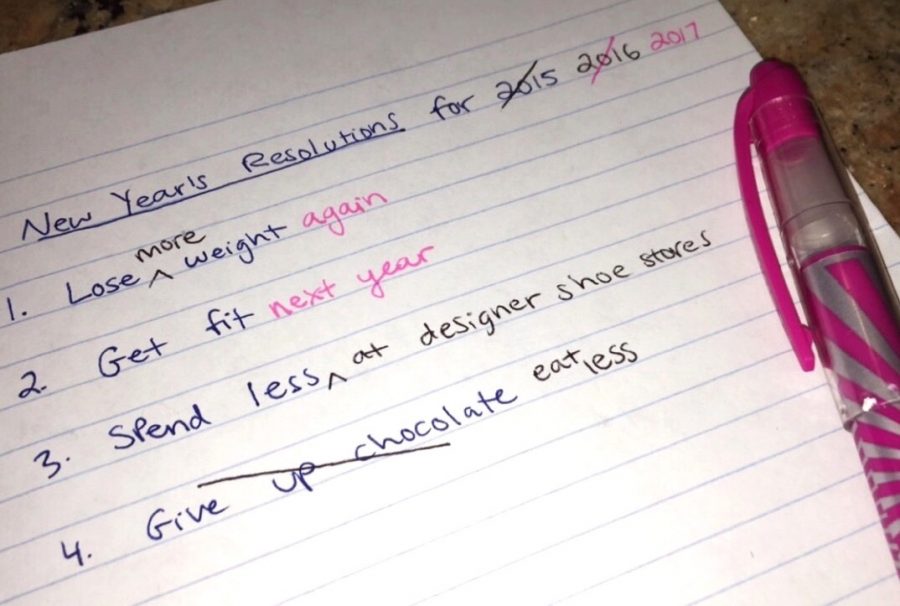

A familiar sight for many: a list of New Year’s resolutions that often go unfullfilled.

March 5, 2017

The best time to start doing different things with your life, making new habits and ending old ones, etc, is the new year. According to researcher John Norcross and his colleagues, 50% of the population makes these resolutions. Among the top resolutions are weight loss, exercise, stopping smoking, better money management and debt reduction. If so many people worldwide use this time as a blank slate, why do almost just as many give up on their resolutions? The first two weeks are great based on statistics, but after that? Things start to go downhill. According to research, people start slipping by February and are back to where they started by December. It seems like such a basic thing — a fresh mindset to go along with the new year — instead, millions give up in such a short amount of time. This brings to question: Are people just plain lazy?

“We often choose the most unrealistic goals as resolutions under the assumption that we can be a completely different person with the snap of a finger in the New Year which is part of the problem,” explained psychotherapist Rachel Weinstein. When we hear about the sometimes exaggerated goals of friends and families set during this same period, the problem itself gets bigger. The marketing advertised around this time focused on these exaggerated goals don’t help much either. In reality, “changes happen in small steps over time.” Weinstein explains.

“You have to rewire your brain and change your way of thinking in order to make resolutions work; A resolution is basically changing your behaviors and habits. Habitual behavior is created by thinking patterns that create neural pathways and memories, which become the default basis for your behavior when you are faced with a choice or decision,” brain scientists such as Antonio Damasio and Joseph LeDoux and psychotherapist Stephen Hayes have discovered.

“Trying to change that default thinking by “not trying to do it,” in effect just strengthens it. Change requires creating new neural pathways from new thinking.” On paper, it sounds simple, but actually putting in the work to achieve your work is an entirely different task that requires hard work and patience.

Habits are automatic, “conditioned” responses. Changing existing habits, such popular resolutions like eating healthier, exercising more, drinking less, quitting smoking, texting less, spending more time “unplugged”, is essentially reconditioning yourself, which is harder than it seems. But, if you change this habits based on science, it becomes a more achievable goal. To change a new habit you essentially have to create a new one. Right now you have created literally hundreds and hundreds of habits that you do not even remember. Creating new ones can’t be that hard.

According to B. J. Fogg and Charles Duhigg, in order to create a new habit, you should to follow these three steps:

1. You MUST pick a small action. “Get more exercise” is not small. “Eat healthier” is not small. This is a big reason why New Year’s resolutions don’t work. If it’s a habit and you want a new one it MUST be something really small. For example, instead of “Get more exercise” choose “Walk 1/3 more than I usually do” or “Take the stairs each morning to get to my office, not the elevator”, or “Have a smoothie every morning with kale in it”. These are relatively small actions.

2. You MUST attach the new action to a previous habit. Figure out a habit you already have that is well established, for example, if you already go for a brisk walk 3 times a week, then adding on 10 more minutes to the existing walk connects the new habit to an existing one. The existing habit “Go for walk” now becomes the “cue” for the new habit: “Walk 10 more minutes.” Your new “stimulus-response” is Go For Walk (Stimulus) followed by “Add 10 minutes.” Your existing habit of “walk through door at office” can now become the “cue” or stimulus for the new habit of “walk up a flight of stairs.” Your existing habit of “Walk into the kitchen in the morning” can now be the stimulus for the new habit of “Make a kale smoothie.”

3. You MUST make the new action EASY to do for at least the first week. Because you are trying to establish a conditioned response, you need to practice the new habit from the existing stimulus from 3 to 7 times before it will “stick” on its own. To help you through this 3 to 7 times phase make it as EASY as possible. Write a note and stick it in your walking shoe that says “Total time today for walk is 30 minutes”. Write a note and put it where you put your keys that says: “Today use the stairs.” Put the kale in the blender and have all your smoothie ingredients ready to go in one spot in the refrigerator.”

If you take these three steps and you practice them 3 to 7 days in a row your new habit will be established. Remember: Hard work and patience are key.