Europe’s Last Dictator Clings to Power

December 2, 2020

On September 23, Alexander Lukashenko was inaugurated for a sixth term in office as the President of Belarus in a small pristine ceremony. Lukashenko has been the head of state for the Eastern European country for over 25 years now, first assuming office in a fair election in 1994. His most recent electoral victory, however, has been mired in controversy. Before the election was even held, protests had already begun to question its legitimacy. Protests only grew when Lukashenko was announced the victor on August 10th. His largest opponent, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, accused Lukashenko of falsifying votes and affirmed that she, in fact, had won the majority of votes. When Lukashenko refused to step down or present an open examination of the election process, public opinion continued to turn against him, and Europe and the rest of the world began to take an interest.

Lukashenko’s authoritarian actions are hardly a surprise for anyone who has been invested in the politics of the former Soviet state. In all six of his elections, only the first one, in 1994, was deemed free and fair by international election officials. During his first term in office, Lukashenko has pursued closer ties with Russia and Vladimir Putin’s government, drafted a new constitution favorable to himself and his allies, took control of the Belarussian national bank, and increased anti-Western rhetoric. Since then, his dictatorial tendencies have only grown, arresting opposition candidates and blocking the freedom of assembly. Several times, The European Union, the United States, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) have disputed the legitimacy of Lukashenko’s government and his actions. The media has taken to calling him Europe’s last dictator in response to his actions in office. His COVID-19 response also failed to garner faith from the public. Initially, Lukashenko was incredibly dismissive of the virus, encouraging farmers to continue working in the fields. He offered steam baths and vodka as useful defenses against viral infection, and refused to take the pandemic seriously. Lukashenko refused to shut the country down and impose a quarantine order, and went ahead with military conscription and the May Day Parade, an event that included 19,000 people. To the people of Belarus, Lukashenko’s actions for the past 25 years in the President’s office proves that he cares more for obtaining and maintaining power than he does for the good of Democracy or the people.

Ironically, one of the few social distancing measures Alexander Lukashenko put in place was for Election Officials and poll watchers, jobs critical to ensuring a fair election that require close scrutiny and contact with ballots. The somewhat innocuous threat to legal elections is indicative of Lukashenko’s treatment of the 2020 election as a whole. Lukashenko had his major opposition opponent, Viktar Babaryka, arrested on trumped up charges of bribery and a coup attempt. He blamed the protests on nonexistent international influence, and detained over 1,300 protesters between May and August. For the first time since 2001, the OSCE was not invited to monitor the Belarusian Election. On Election Day itself, the President cut off all transportation into Minsk, Belarus’ capital city, and partially blocked internet access. Immediately after polls closed, Lukashenko was announced the victor in such a monumentous landslide that even media sympathetic to the President thought the numbers were fake. It was then that protests picked up in full force.

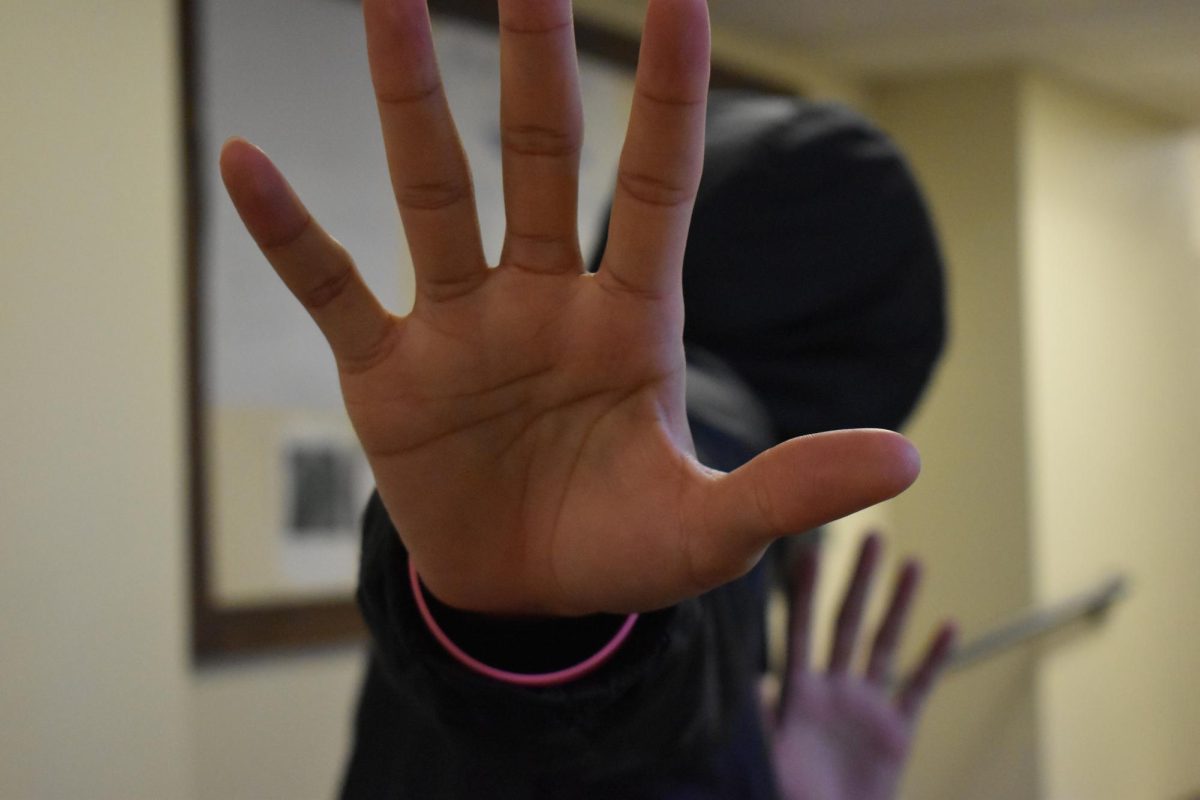

Protests calling for a fair election and questioning the President’s validity had begun long before the election. Dubbed the “Slipper Revolution” after a Russian children’s poem, protests began in earnest in May, and grew in size and intensity in the months leading up to the election. Once the results were called, however, the outcry truly reached full force. The night of election saw some of Belarus’ largest protests since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Law enforcement cracked down on protests with rubber bullets and grenades. The opposition candidate was forced to flee to Lithuania. From then on, protests only grew and policing only worsened. Through it all, Lukashenko has refused to step down, telling a crowd in Minsk that would have to kill him to get another election. Large strikes have been called, and Russian military forces have begun to enter Belarus to aid Lukashenko’s government. Following the fraudulent election, tensions in Eastern Europe have only grown, as Lukashenko refuses to yield power and Russia is anxious to increase its influence in Europe.

For as dramatic at it all sounds, the events in Belarus have not reached the ears of most of America. “I had no idea any of this was going on,” says Estelle Hegenbarth ’21. “I barely know what Belarus is!” Yet those who have heard of the events have legitimate fears. “The more elections that are rigged and successfully get away with it, the more rigged elections there will be,” says Sarah Stovicek ’21. Ryan Wood, Teacher Assistant for European & Mediterranean History and Global Politics, agrees. “It’s indicative of a scary global trend towards authoritarianism,” he intones. China has continued to rise on the Global Stage under the leadership of Xi Jinping, and nations like Hungary have used the COVID epidemic to seize power through non-democratic means. Donald Trump has spurred fears of autocracy in many centrist and left leaning citizens, and his attempts to discredit the 2020 election do little to assuage those claims. As scary as the situation in Belarus is on its own, it is important to recognize that it is a symptom of a greater problem in global politics. Democracy is at risk of dying, and deliberate action is necessary to take it off the path towards destruction.